Gone are the days when ransomware operators were happy with

encrypting files on-site and more or less discretely charged their

victims money for a decryption key. What we commonly find now is

encryption with the additional threat of leaking stolen data,

generally called Double-Extortion (or, as we like to call it: Cyber

Extortion or Cy-X). This is a unique form of cybercrime in that we

can observe and analyze some of the criminal action via ‘victim

shaming’ leak sites.

Since January 2020, we have applied ourselves to identifying as

many of these sites as possible to record and document the victims

who feature on them. Adding our own research, analyzing, and

enriching data scraped from the various Cy-X operators and market

sites, we can provide direct insights into the victimology from

this specific perspective.

We must be clear that what we are analyzing is a limited

perspective on the crime. Nevertheless, the data gleaned from an

analysis of the leak-threats proves to be extremely

instructive.

We’ll refer to the listing of a compromised organization on a

Cy-X leak site as a ‘leak threat’. The numbers you’ll see in most

of the charts below refer to counts of such individual threats on

the onion sites of the Cy-X groups we’ve been able to identify and

track over the last two years.

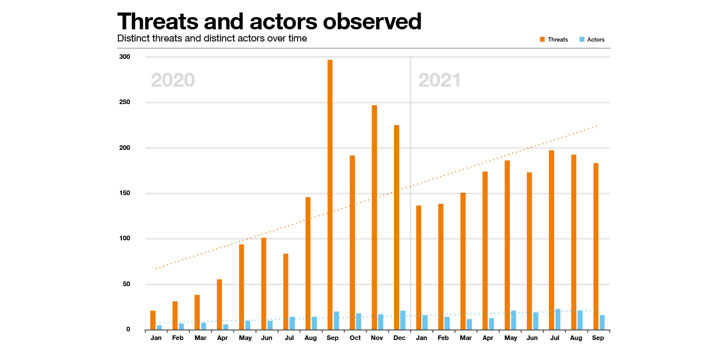

A boom in leak threats

Despite the vagaries of the environment we’re observing, the

number of unique leaks serves as reliable proxy for the scale of

this crime, and its general trends over time. We observed an almost

six-fold increase in leak-threats from the first quarter of 2020 to

the third quarter of 2021.

|

| Source: Orange Cyberdefense Security Navigator 2022 |

Striking where the money is: Leak threats by

country

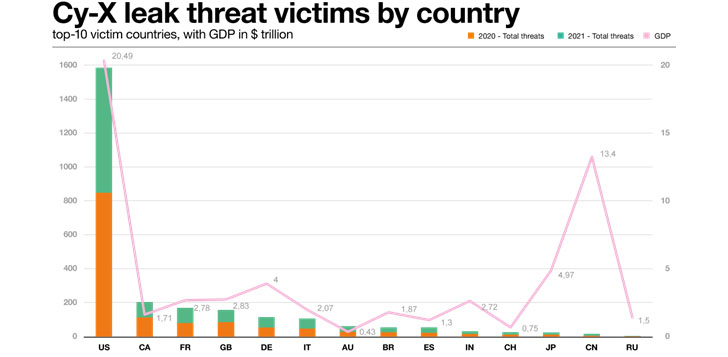

Let’s take a look at the countries the victims operate in.

|

| Source: Orange Cyberdefense Security Navigator 2022 |

In the chart above we show the 2020 and 2021 leak threat counts

per country, for the top 10 countries featured in our data set. We

also show the estimated Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for the 12

wealthiest countries[1].

The top victim countries have remained relatively constant

across our data set. As a general rule of thumb, the ranking of a

country in our data set tracks the relative GDP of that country.

The bigger the economy of a country, the more victims it is likely

to have. Indeed, eight of the top ten Cy-X victim countries are

among the top 10 economies in the world.

The conclusion we draw from this, is that the relative number of

victims in a country is simply a function of the number of online

businesses in that country. This does not prove definitively that

Cy-X actors do not deliberately attack targets in specific

countries or regions from time to time. It’s also not to say that a

business in a high-GDP country is more likely to be attacked than a

victim in a low-GDP country (since, with more businesses exposed

within that country, the probabilities even out).

In our view, the take-away from this data is simply that

businesses in almost every country are being compromised and

extorted. Logically, the more businesses a country has, the more

victims we will see.

Exceptions to the rule

Having said that, we’ve taken the liberty of including India,

Japan, China and Russia in the chart above, as counterexamples of

large-GDP countries that rank low on our Cy-X victims list.

India, with a projected 2021 GDP of $ 2.72 trillion, and China

with $ 13.4 trillion, appear underrepresented, which might be due

to several reasons. India, for example, has a huge population and

correspondingly large GDP, but the GDP per capita is lower, and the

economy generally appears less modernized and digital, meaning

fewer online businesses to target. It could be that criminals doubt

that Indian businesses could or would pay their dollar-based

ransoms. The language might also play a role – businesses that

don’t communicate in English are more difficult to locate,

understand, navigate, and negotiate with, and their users are

harder to exploit using commoditized social engineering tools.

Japan, as another obvious exception to our rule, has a highly

modernized economy, but will present criminals with the same

language and culture barriers as China and India, thus possibly

accounting for the low prevalence in our victim data.

The conclusion here is that Cy-X is moving from English to

non-English economies, but slowly for the time being. This is

probably the logical result of the growing demand for victims

fueled by new actors, but it might also be the consequence of

increased political signaling from the USA, which may be making

actors more cautious about who they and their affiliates

exploit.

Regardless of the reasons, the conclusion here once again needs

to be that victims are found in almost every country, and countries

who have hitherto appeared relatively unaffected cannot hope that

this will remain the case.

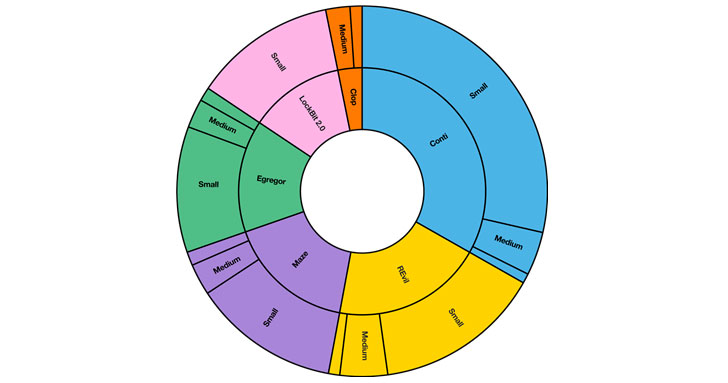

One size fits all: No evidence of ‘big game

hunting’

In the chart below we show the number of victims by business

size in our data set mapped to the top 5 actors. We define

organization sizes as small (1000 or less employees), medium

(1000-10,000) and large (10,000+).

|

| Source: Orange Cyberdefense Security Navigator 2022 |

As shown, businesses with less than 1,000 employees are

compromised and threatened most often, with almost 75% of all leaks

originating from them. We’ve seen this pattern consistently in our

leak-threats data over the last two years, by industry, country,

and actor.

The most obvious explanation for this pattern is again that

criminals are attacking indiscriminately, but that there are more

small businesses in the world. Small businesses are also likely to

have fewer skills and technical resources with which to defend

themselves or recover from attacks.

This suggests again that any and every business can expect to be

targeted, and that the primary deciding factor of becoming a leak

site victim is the ability of the business to withstand attack and

recover from compromise.

It’s worth also noting that, since the crime we’re investigating

here is extortion, and not theft, it is the value of the impacted

digital asset to the victim that concerns us, not the value of the

data to the criminal.

Any business that has digital assets of value can therefore be a

victim. Neither small size nor the perceived ‘irrelevance’ of data

will offer significant protection or ‘fly under the radar’.

This is just an excerpt of the analysis. More details like the

threat actors identified or the industries targeted most (as well

as a ton of other interesting research topics) can be found in the

Security Navigator[1]. It’s available for

download on the Orange Cyberdefense website, so have a look. It’s

worth it!

Note — This article was

written and contributed by Carl Morris, lead security researcher, and Charl van der Walt,

head of security research, of Orange

Cyberdefense.

References

- ^

Security

Navigator (orangecyberdefense.com)

Read more https://thehackernews.com/2022/01/a-trip-to-dark-site-leak-sites-analyzed.html