The iPhone of New York Times journalist Ben Hubbard was

repeatedly hacked with NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware tool over a

three-year period stretching between June 2018 to June 2021,

resulting in infections twice in July 2020 and June 2021.

The University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab, which publicized[1]

the findings on Sunday, said the “targeting took place while he was

reporting on Saudi Arabia, and writing a book about Saudi Crown

Prince Mohammed bin Salman.” The research institute did not

attribute the infiltrations to a specific government.

In a statement[2]

shared with Hubbard, the Israeli company denied its involvement in

the hacks and dismissed the findings as “speculation,” while noting

that the journalist was not “a target of Pegasus by any of NSO’s

customers.”

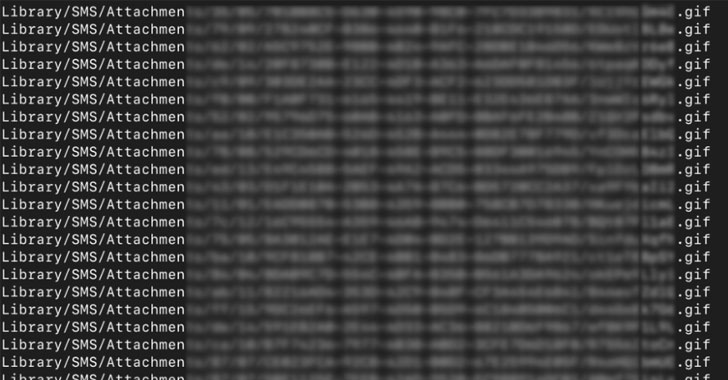

To date, NSO Group is believed to have leveraged at least three

different iOS exploits — namely an iMessage zero-click exploit in

December 2019, a KISMET[3]

exploit targeting iOS 13.5.1 and iOS 13.7 starting July 2020, and a

FORCEDENTRY[4]

exploit aimed at iOS 14.x until 14.7.1 since February 2021.

It’s worth pointing out that Apple’s iOS 14 update includes a

BlastDoor Framework[5]

that’s designed to make zero-click exploitation more difficult,

although FORCEDENTRY expressly undermines that very security

feature built into the operating system, prompting Apple to

issue an update[6]

to remediate the shortcoming in September 2021.

|

| FORCEDENTRY exploit on the phone of the Saudi activist |

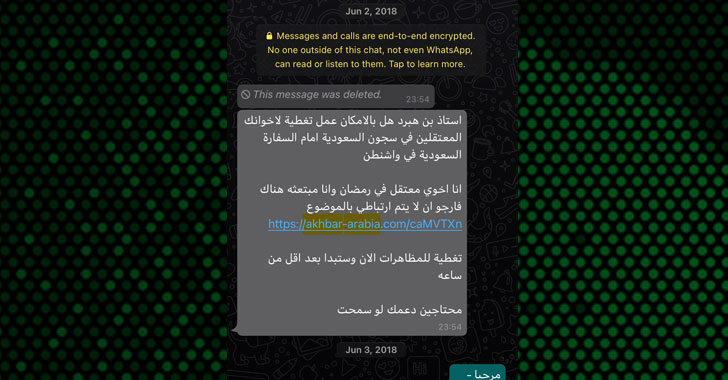

Forensic investigation into the campaign has revealed that

Hubbard’s iPhone was successfully hacked with the surveillance

software twice on July 12, 2020 and June 13, 2021, once each via

the KISMET and FORCEDENTRY zero-click iMessage exploits, after

making two earlier unsuccessful attempts via SMS and WhatsApp in

2018.

The disclosure is the latest in a long list of documented cases

of activists, journalists, and heads of state being targeted or

hacked using the company’s “military-grade spyware.” Earlier

revelations in July laid bare an extensive abuse[7]

of the tool by several authoritarian governments to facilitate

human rights violations around the world.

The findings are also particularly significant in light of a new

interim rule passed by the U.S. government that requires[8]

that companies dabbling in intrusion software acquire a license

from the Commerce Department before exporting such “cybersecurity

items” to countries of “national security or weapons of mass

destruction concern.”

“As long as we store our lives on devices that have

vulnerabilities, and surveillance companies can earn millions of

dollars selling ways to exploit them, our defenses are limited,

especially if a government decides it wants our data,” Hubbard

wrote[9]

in the New York Times.

“Now, I limit the information I keep on my phone. I reboot my

phone often, which can kick out (but not keep off) some spy

programs. And, when possible, I resort to one of the few

non-hackable options we still have: I leave my phone behind and

meet people face to face,” Hubbard added.

References

- ^

publicized

(citizenlab.ca) - ^

statement

(www.nytimes.com) - ^

KISMET

(thehackernews.com) - ^

FORCEDENTRY

(thehackernews.com) - ^

BlastDoor Framework

(thehackernews.com) - ^

issue an

update (thehackernews.com) - ^

extensive abuse

(thehackernews.com) - ^

requires

(thehackernews.com) - ^

wrote

(www.nytimes.com)